Volcanic Blast Likely Killed and Preserved Juvenile Fossil Plesiosaur

Amid 70-mile-an-hour winds and freezing Antarctic conditions, an American-Argentine research team has recovered the well-preserved fossil skeleton of a juvenile plesiosaur--a marine reptile that swam the waters of the Southern Ocean roughly 70 million years ago.

The fossil remains represent one of the most-complete plesiosaur skeletons ever found and is thought to be the best-articulated fossil skeleton ever recovered from Antarctica. The creature would have inhabited Antarctic waters during a period when the Earth and oceans were far warmer than they are today.

James Martin, curator of vertebrate paleontology and coordinator of the paleontology program at the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology's Museum of Geology, announced the plesiosaur bones was to be unveiled at the museum on Dec.13.

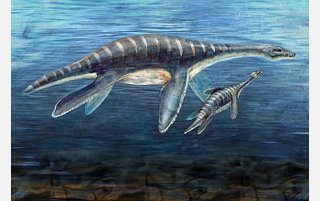

The long-necked, diamond-finned plesiosaurs are probably most familiar as the legendary inhabitants of Scotland's Loch Ness, although scientific evidence indicates the marine carnivores have been extinct for millions of years. But when the creatures were alive, their paddle-like fins would have allowed them to "fly through the water" in a motion very similar to modern-day penguins.

Martin, an expert on fossil marine reptiles, co-led the 2005 expedition to Antarctica that recovered the plesiosaur. Judd Case, of Eastern Washington University, and Marcelo Reguero of the Museo de La Plata, Argentina, were also co- leaders.

The US National Science Foundation (NSF) and the Instituto Antártico Argentino, directed by Sergio Marenssi, funded the expedition. The Argentine Air Force provided helicopter support.

NSF manages the U.S Antarctic Program, which coordinates all U.S. research on the southernmost continent. The White House has designated NSF as the lead federal agency for the International Polar Year, a two-year global research campaign in the polar regions that begins in March 2007.

Preserved by a volcanic blast?

After it was prepared in the United States, Martin said, the specimen was discovered tobe the 5-foot-long (1.5 meters) skeleton of a long-necked (elasmosaurid) plesiosaur. An adult specimen could reach over 32 feet (10 meters) in length. Most of the bones of the baby plesiosaur had not developed distinct ends due to the youth of the specimen, he said.

But the animal's stomach area was spectacularly preserved. Stomach ribs (gastralia) span the abdomen, and rather than being long, straight bones like those of most plesiosaurs, these are forked, sometimes into three prongs. Moreover, numerous small, rounded stomach stones (gastroliths) are concentrated within the abdominal cavity, indicating stomach stones were ingested even by juvenile plesiosaurs to help maintain buoyancy or to aid digestion.

The skeleton is nearly perfectly articulated as it would have been in life, but the skull has eroded away from the body. Extreme weather at the excavation site on Vega Island off the Antarctic Peninsula and lack of field time prevented further exploration for the eroded skull.

The researchers speculate volcanism similar to the massive eruption of Mt. St. Helens in Washington in 1980, may have caused the animal's death. Excavation turned up volcanic ash beds layered within the shallow marine sands at the site, and chunks of ash were found with plant material inside. That suggests a major blow-down of trees as was observed when Mt. St. Helens erupted. Either the blast or ash dumped into the ocean, the scientists say, may have caused the baby's demise. Moreover, silica released from the ash allowed spectacular preservation of the skeleton.

Bookmark http://universeeverything.blogspot.com/ and drop back in sometime.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home